Should Data Expire? Entropy and permanence in digital landscapes

This essay was initially presented as a talk at https://scholar.social Summer School 2022, and AntiUniversity Now 2022, and has been rewritten and edited for Solar Protocol.

When considering our personal data, we might first think of key facts about ourselves: our name, age, demographic information, and anything else collected by official forms. If we expand this definition, we can include the memory crumbs which trail behind us as we go about our daily lives. Our texts, emails, photos, videos, voice notes — these artefacts which are created both incidentally and on purpose end up telling the story of our lives. It’s this expanded definition of personal data that I’m going to use in this essay. I’m also only talking about personal data specifically — I have intentionally excluded commercial uses of, and attitudes towards, data, its collection, storage, and use.

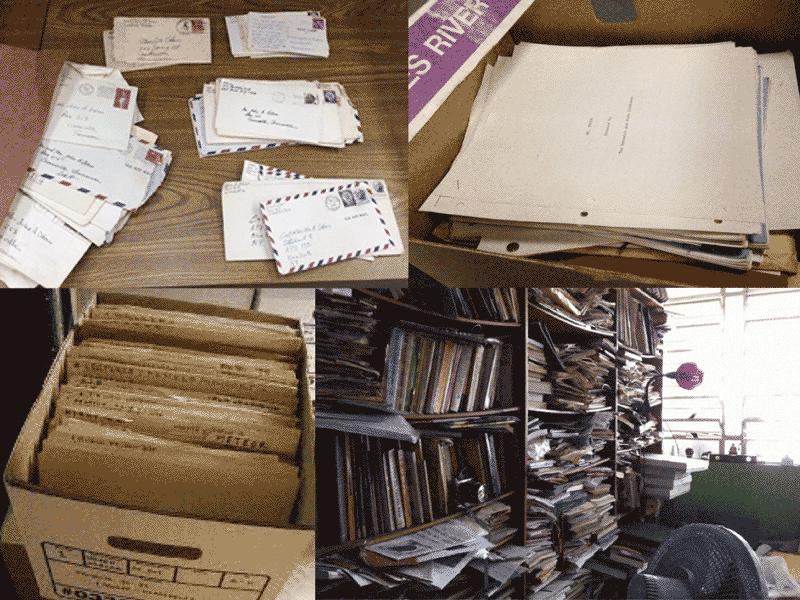

In the pre-digital world, our personal data took up a lot of space. In fact, it took up exactly as much space as the thing that it was. If you wrote a letter, it would take up exactly one letter’s worth of space on your desk, in your drawer, in a folder, or in your bin. If you wanted to create a copy of a document, that copy would again take up the same amount of space as the original. There was no abstraction in form between the data, what it represented, and the space it took up. Hard copy storage is grounded in the material.

Image sources (clockwise, starting top left)

1

2

3

4

Image sources (clockwise, starting top left)

1

2

3

4

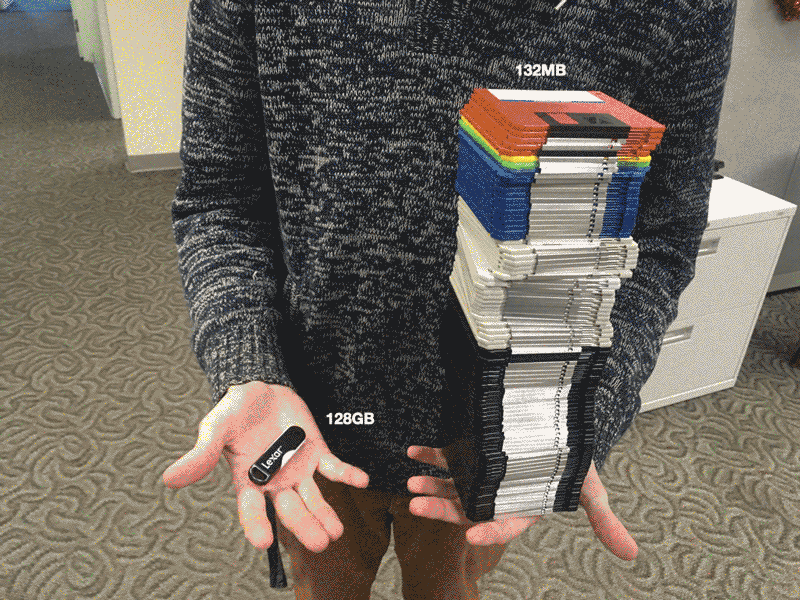

Digital technologies have undermined a 1:1 relationship between stored data and the scale and form of its storage medium. As magnetic tape, floppy disks, and eventually computer hard drives developed, the amount of data we could store in the same office, drawer, cabinet, or suitcase expanded exponentially. While storage has not yet been entirely divorced from physicality — there is still a relationship between digital file size and the amount of storage space it takes in the real world — we can afford to be a lot more liberal about what we choose to keep. As storage technology has continued to develop, it has become almost impossible for most people to perceive the relationship between physical size and storage capacity.

Image source

5

(annotations my own)

Image source

5

(annotations my own)

The physicality of storage, by which I mean the space it materially takes up and the quality of said space, is directly related to how we might curate, organise, sort, and store the data it contains. Consider an expansive DVD collection — this data takes a very physical form, but is still much more compact than VHS tapes, and even smaller still than reels of film. For someone with a particularly large film collection, their DVDs might take up a wall of a room in their home. This method of storage means that they exist alongside their DVDs — they see them every day. They might choose to sort them in a way that’s visually pleasing, or alphabetical, or chronological, so that they’re satisfied at how organised their DVDs are every time they see them. They might be forced to forgo a purchase of a new DVD simply because they don’t have space for any more. They might decide to sell some to make room for more DVDs (or something else entirely). The DVD collector in this scenario has a habitual and incidental relationship with the data they’re storing. They revisit it regularly, and can easily understand how the size of their collection relates to the amount of data (films) they have stored, as well as the capacity they have for storing other things.

Before digital storage, two main factors influenced the data, or artefacts, we created, and those that we kept: ease of creation (or reproduction) and physical storage space. Moving into early-digital, pre-cloud contexts, we were less influenced by how easy it was to make something (writing a letter is a lot faster using a word processor than writing by hand), but still quite heavily influenced by how much space it took to store something (if you fill up a USB stick, you need to either delete something, move something to more permanent, archival storage, or get another USB stick). In the contemporary context, it is both easy to create or reproduce an artefact and storage is no longer something with which we have an incidental, habitual, spatial relationship. There are no longer ‘natural’ limiting factors on our capacity to create and store artefacts.

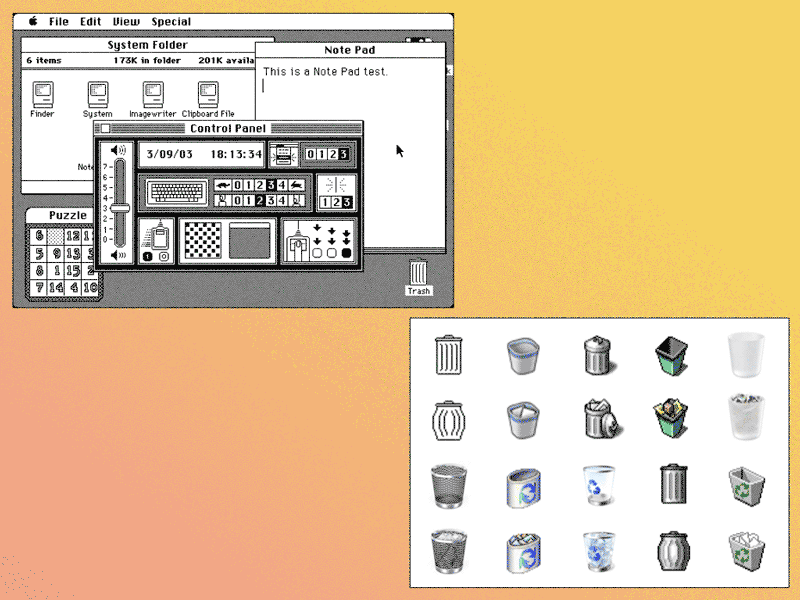

As storage becomes less grounded in its physicality, it’s harder to grasp what it means for a file to be ‘large’, or to keep track of just how many artefacts we’re holding on to. Part of the attempt to address this disconnection is through the use of skeuomorphic design. For something to be skeuomorphic, its design must echo elements of that same object when made from another material, or used in a different context. In this case, we’re referring to digital representations of things which are familiar for their non-digital function, like a note pad, or a bin. When desktop computers were entering the mainstream, their interfaces utilised a wide range of skeuomorphic objects in order to help new users bridge the gap between the paper office and the digital office.

" Images source (same for both)

6

" Images source (same for both)

6

Skeuomorphic folders are designed to look just like the folders you’d find in a filing cabinet. Deleting a file requires you to drag and drop it in the trash can sitting at the corner of your desktop. To save something, you invoke the power of the floppy disk. In the early days of widespread computer use, this proved a powerful tool for assisting the general population in adapting to new technologies. However, these skeuomorphs rapidly shed their utility. As time passes, new generations are born who possess no frame of reference for the physical counterparts of said skeuomorphs.

They see it like one bucket, and everything’s in the bucket

A 2021 Verge article 7 laid bare an apparent lack in the technical skill of Gen Z university students. The article claims that young adults are entering higher education with no innate understanding of how digital file systems work. It (and a similar article in The Byte from around the same time 8 ) asserts that many Gen Z and younger think of computer storage as an infinite, searchable bucket. And why should they think any differently? Those who have grown up with efficient, powerful search tools and expanding access to cloud storage, may have never had to develop an effective method of structuring their own data. They have no inherent understanding of the physicality of data, and how managing, curating, and organising that data has previously been absolutely necessary to accommodate storage limitations.

Image sources: Servers with Cloud graphic overlay

9

Image sources: Servers with Cloud graphic overlay

9

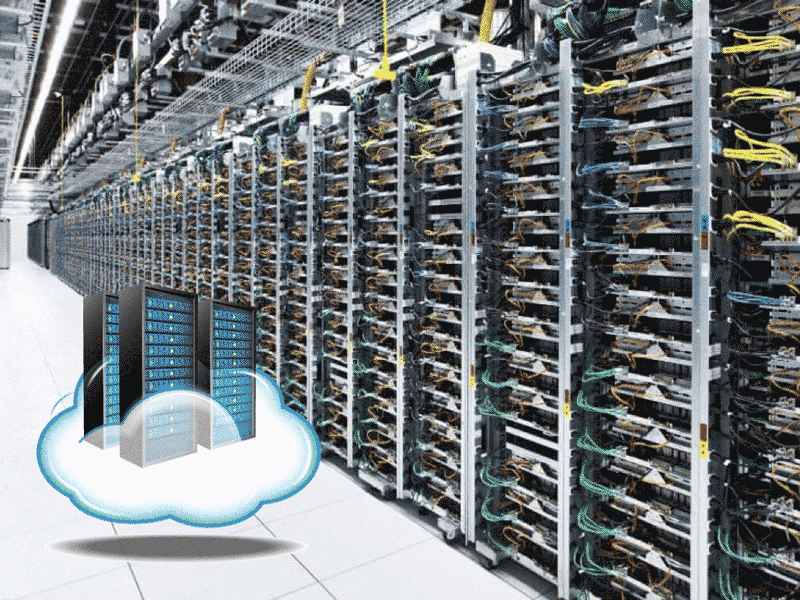

One of the biggest shifts in how we store our personal data has been that we no longer keep it in our own homes. Cloud storage has been widely adopted, meaning we no longer have to face the reality of not physically having enough storage capacity of our own — we can always borrow more (for a price). The physical limitation of space on our storage habits has been replaced with a purely financial subscription model, a virtual asset with unlimited flex, rather than a material, spatial expansion. Digital storage has become perceived as an infinite resource.

The cloud is a wispy, intangible, dream-like metaphor

The cloud is removed from our everyday environment, conjuring images of our photos, emails, and voice memos floating around in the sky above us. It takes a weight off our chests, and casts it to the heavens. The cloud is somewhere else, and any problems created by simply having too much stuff are now someone else’s problems. When resources are virtual, infinite, and expandable via subscription, the consequences of overconsuming are indirect and out of sight. We are rarely confronted with the environmental reality of our reliance on datacentres. 10

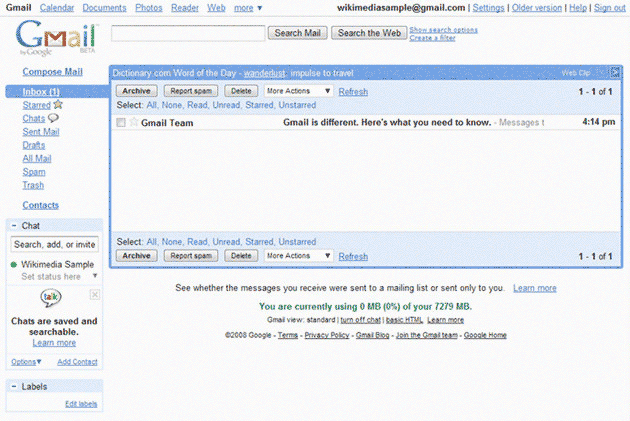

Largely, this trajectory was pushed by Google. Following the introduction of Gmail in 2004, which provided 500 times more storage than Hotmail (weighing in at a hefty 1GB per user at launch), our relationship with what’s possible or practical to save changed forever. Initially, Gmail didn’t even include a delete button 11 . Not only was it no longer necessary to delete emails regularly to make space in your inbox, but it was actually not even possible . This shift broke everyone’s deletion habit — it ended the ritualistic appraisal of what should be kept, and ushered in a default in which literally everything should.

Early Gmail interface.

Early Gmail interface.

Google was only able to afford to offer such expansive storage to everyone who wanted it, for free, because the company scraped and extracted value from everything we stored with them. The data they collected from everyday communications was used to sell relevant, highly targeted advertising space. Google ony stopped using emails in this way in 2017 12 — 13 years after its launch.

97% of adults use cloud storage for some or all of their photos

In a study commissioned by Fujifilm in March 2022 13 , 97% of all adults surveyed said that they use cloud storage for some or all of their photos. Only 12% of those surveyed spend money on additional storage, and 7 out of 10 admitted to transferring old photos onto new devices without filtering or organising them in any way. The survey also queried how often participants would go back and review their collections — the average rate was only once a month.

The study was intended to determine whether younger adults feel more precarious about their memories in the context of COVID changing how we interact with technology. The study’s conclusion was that they do, because they hold on to more photos than other demographics surveyed; with over a third of those surveyed citing concern over forgetting memories and events as the reason they don’t delete their images. An additional third of those surveyed said looking at past memories helps to brighten their day, despite the low rate at which those memories are reviewed. This infrequent revisiting is the point I find most salient here. If these photos are truly a crutch to bolster our memory, and boost our mood, wouldn’t we spend a bit more time, well, remembering?

Entrusting our memories to the cloud, and with such large collections of personal data being quite commonplace, many people rely heavily on cloud storage providers to keep their memories safe. In an informal survey of friends, colleagues, and followers on federated networks (86 respondents), around half reported having photo collections on their phones of more than 5,000 images, with just over 70% reporting more than 1,000 images stored. Collection habits have vastly outgrown typical local storage capacities, so often it’s not possible to have total control of data storage without significant investment in local, offline capacity. With this level of trust in cloud storage, it’s easy to think it’s unlikely for anything to go wrong, and that it will always be there. Unfortunately, that’s simply not the case.

In 2019, news broke that MySpace had lost 12 years of music during a server migration 14 . Many of these songs were never uploaded anywhere else — MySpace had been the permanent record of these artists’ musical output. It’s estimated that up to 50 million tracks were lost in this incident alone. To put into perspective just how much data is stored by social media companies like MySpace, Meta (formerly known as Facebook) has continually expanded its first data centre, built in 2011, to a size of more than 3 million square feet as of 2018 15 . According to their own maps 16 , they have 21 data centres currently in operation, across North America, Europe, and Asia.

MySpace’s servers, just like any other computer, are and were subject to the same entropy as anything which has a material form. Just because cloud storage isn’t something we can immediately see and touch doesn’t mean it lacks a physical presence somewhere on the planet. Cloud storage is still subject to fire, flood, earthquake, or simply decay over time — all of which can be mitigated to an extent but not entirely prevented 17 . Anything stored in the cloud could be lost, just as a letter given to you as a kid could fall down the side of your desk, or get burnt in a fire, or have a cup of water spilled onto it, or simply fade until the ink is no longer legible at all.

I consider our collections of personal data to be a kind of informal archive 18 19 . By informal, I mean that in contrast to a traditional archive collection, it’s not professionally looked after, sorted, or contextualised. Formal archives have someone whose job it is to know them. There is an archivist, or a team of archivists, who are aware of all of the parts and how they fit together. Informal archives (of the kind we’re contributing to every time we send a text, email, or take a photo) are unsorted and largely left untouched. The information isn’t studied, or stored in a way which is easy to access effectively. Our personal collections are buckets of information which have no logical relationships, no archivist, and no contextual anchors by which to understand them.

Archives teach us about what came before

Archives hold key information which paints a picture of the humans of the past so we can better understand our histories today 20 21 . When we create an archive of ourselves, we’re contributing to a kind of historicisation of our very near past. It freezes in amber a version of ourselves we’ve not yet had time to grow away from. Formal archives are subject to regulation and data protection laws, removing them temporally from the person or people who are documented within them. Our informal, personal collections are not subject to this same kind of removal — they can be used to inform decisions about relationships with ourselves and others almost in real time.

One of the most common ways to access information in our personal collections is through algorithmic ‘on this day’ features, now built in to most smartphones and mainstream social media platforms. This kind of tool was developed because we love to think about ourselves. We love to reminisce on good memories and (most importantly for the social platforms which developed this style of technology) we’re likely to reshare particularly positive or impactful moments with our friends. Unfortunately, due to the totally removed aspect of human curation when it comes to working with our personal collections, it’s just as likely that formative bad memories will be dug up and presented to us as good ones. This is an example of algorithmic cruelty.

Both our formal and informal archives have a complex relationship with being publicly accessible. Formal archives are made public often through institutions, which may restrict access to certain parts in order to protect the subjects of those archives. It’s common practice for archives to be sealed for 100 years when they refer to identifiable individuals in order to avoid impacting the everyday lives of those documented in the collections. Our informal archives, however, are often self-published. We become our own curators, choosing a highlight reel to present to the wider online public on our profile pages. We present an idealised, aestheticised version of ourselves, and then puppet that self as part of our social interactions in the online landscape.

Sharing our informal collections through our own curated lens changes our image of self. We start to blur the edges between our whole, offline, flawed self, and our curated, online, idealised self. We’re playing a roleplaying game we never realised we signed up for, and it’s one that can bleed outwards into our offline lives too. We start to treat our curated, projected collection as if it is reflective of the whole, and see others in the same light.

It used to be commonplace to have a ‘screenname’ or ‘username’. Online, we would consensually enter the role of someone else, our online character, who would be distinct from our offline self. Our screen persona could embody characteristics about ourselves that we mediated offline, or be a channel for exploring things our offline selves would never do. It was protected in its distinction. With the dawn of Facebook, we started to see an increase in usage of our offline names (or ‘real names’) in online spaces. Mark Zuckerberg explicitly pursues a ‘real name policy’ on Facebook, and it’s common for those who change their name, or go by a different name, to have their account deactivated if Facebook detects any incongruence. 22

This usage of ‘real names’ in online spaces helped collapse the distinction between our online and offline selves. We started logging on to roleplay as a version of our self, not as a character with a totally different identity. Suddenly, the things we did online started bleeding out into our real life social sphere. Not only did Zuckerberg have a vision of an internet where everyone extends their offline self in a networked plane, but he asked people to bring their offline social connections into the online space. He was aiming to replicate communities which formed through lived experience, through proximity, or connections which were probably only supposed to be fleeting, in an online space. Online spaces, especially those which consider themselves ‘platforms’, introduce a collapse of distance, context, and a binary vision of whether someone is your ‘friend’. The process of replicating these offline connections expedited the ‘leak’ of our offline lives into our online lives, and vice versa.

However, most Gen Z don’t remember a time before Facebook. For people with this experience, lines between ‘offline self’ and ‘online self’ have always been blurred, each informing the other. Online is no longer a separate space in which to escape or explore fantasy, but an extension of the physical neighbourhood, educational institution, or workplace you frequent every day. It could be argued that ‘real name’ policies only impact the sites on which they are enforced, but like anything with mass adoption, the habits of users have shifted to reflect its impact on how we view our online profiles. There is now an expectation in many online spaces that users will present a version of their ‘real’ or offline selves, rather than a pseudonymous alter.

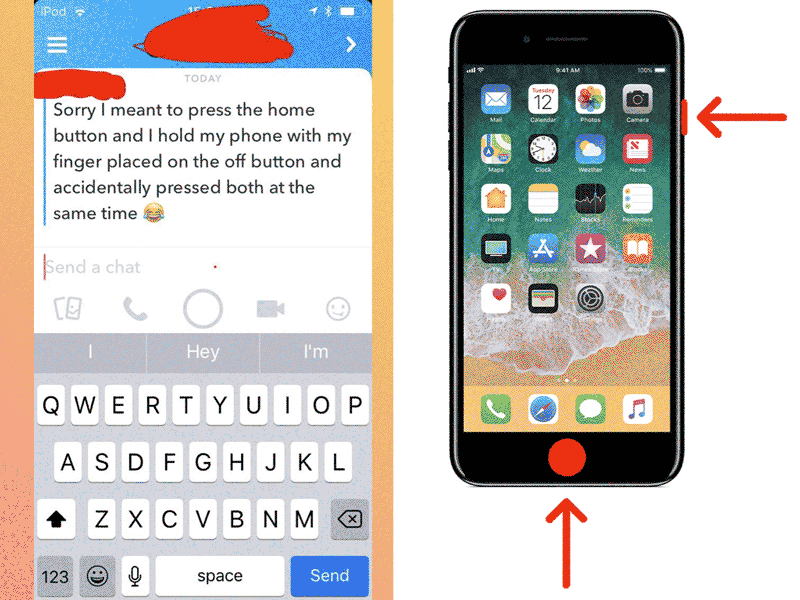

Taking a screenshot is a way of legitimising something

It’s a flag in the sand that says ‘I want to save this, and look at it later. This is important enough.’ For something to be screenshot-worthy, it’s crossed the threshold that you not only want to keep it, but you want to know where it is. It reached something within you that makes the ongoing automated collection of our movements as we traverse the internet no longer sufficient for this kind of recollection, and you want to be able to step back inside this moment — either because it’s important to other people or because it’s important to you.

Platforms like Snapchat enact a short-form expiry policy for messages shared through their service. This brings a sense of immediate loss, heightening the feeling that whatever you’re looking at is slipping through your fingers. This sense of immediate loss encourages screenshot-based activation — we want to hold onto as much as we can when we’re talking to someone we care about, or experiencing heightened emotions together. They encourage the natural curation-of-memory behaviour that’s absent in so much of how we interact online — this is happening now , and then it’s gone forever.

Image sources (left to right):

23

24

Image sources (left to right):

23

24

It can be uncomfortable to find that something you shared, which you thought would be fleeting, has been saved by someone else without your knowledge or consent, especially when engaging with text-based chat. Chat conversations move quickly and can be more unfiltered and candid than something you’d publish purposefully. In pursuing a direct analogue to real-life fleeting conversation, Snapchat encourages the kind of spontaneous emotional traversal common to one-on-one, private conversations offline. Their service cultivates a sense of safety in the transience of the information transmitted between users.

The sense of intimacy that fleeting conversation cultivates means that it can feel like a betrayal to find out that something you shared in confidence has been screenshotted and rebroadcast more widely, out of the context of the original conversation. To try and combat this sense of betrayal, Snapchat implemented notifications that informed the other person that you had screenshotted something. Yet as soon as this had been implemented, we came up with ways to circumvent these notifications. 25 In addition to what we capture in order to rebroadcast, screenshots take on another quality when they contribute to our collected archive of personal data. They contribute to our sense of self.

The things we choose to keep hold of shape us. They remind us what we’ve been through, where we’ve travelled, who we’ve met and what we’ve done, in ways that when unaided, we tend to forget. 26 27 A pebble from an important beach holds so much more within it than just the stone itself. When so many of our memories take place digitally, it’s no wonder that we’ve devised a method to take home souvenirs from our digital escapades.

We only have so much capacity to remember

Many of the tools we’ve built over time are explicitly to aid in supporting our memories. In theory, what we choose to preserve is kept safe, a kind of highlight reel — and maybe this was true when we had limited resources to create, store, and recover precious memories. In a time when taking these snapshots takes very little energy, time, or judgement, our ability to discover, recall, and properly sort our collected memories is impaired.

When these memories are published, we contribute to a shared memory bank — a narrative of the world created by, for, and within, a kind of collective consciousness. Like the formal archive, we turn to this collective externalised memory to form our narrative about what it’s like to live in the world, what it’s been like in the past, and the decisions we make moving forwards.

When our self image, and the images we form of others, are externalised, they’re subject to the whims of that external environment. When that external environment is controlled, owned, or stewarded by a private company, we can no longer trust that our own externalised self isn’t being used simply to manipulate us into furthering the commercial goals of said company. Thinking back to the emergence of ‘on this day’ tools — these use our self-image in order to generate clicks and retain eyeballs on commercial platforms. It’s our self being chewed up and fed back to us in order to sell advertising space.

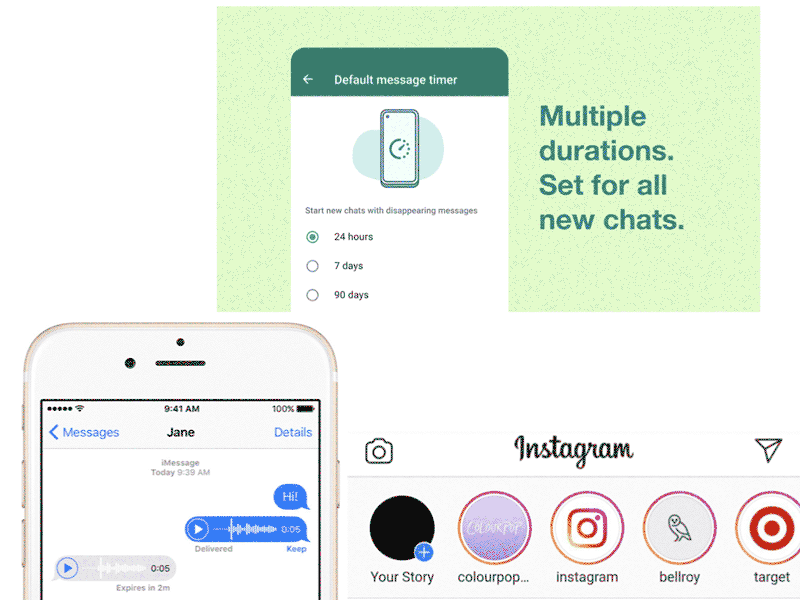

What would the world be like if all personal data had some kind of built in expiry date? We’ve already touched on the impact that Snapchat’s expiry feature has on how we feel about conversations made using its platform. Elsewhere, expiration is implemented through optional disappearing messages (an increasingly common feature across many chat platforms), iMessage audio files disappearing after two minutes unless you choose to keep them forever, and Instagram stories which vanish after 24 hours. Interestingly, in the case of Instagram stories, their transience is performed — the uploader can still access stories after their expiry in their ‘stories archive’. While Instagram stories appear outwardly to subscribe to the ethos of data expiry, in reality it just creates another mass, unsorted archive (by any metric other than chronologically).

Image sources (top to bottom, left to right):

28

29

Image sources (top to bottom, left to right):

28

29

Giving data a limited lifespan by default is an approach which is usually only applied to communications that are designed to feel more transient, such as digital analogues to spoken chatter, or services which encourage a momentary capture of your ‘now’. Digital artefacts like emails, photos, and videos (which aren’t captured to share immediately) are seemingly never included in the conversation about expiration, perhaps because they are products of analogue processes which were designed specifically for the purpose of recording our lives.

How could we go about applying an expiry protocol to these artefacts? First, I think their erasure must be complete. Nobody, anywhere should have a copy of what was written or captured once it has expired. I think this completeness is absolutely essential in order for the erasure to have a real impact on how we feel about the things we choose to keep. I also think the period between creation and deletion needs to be long enough that you’re done with short-term processing before the data slips away. You should have had enough time to create it, think about it a little bit, come back to it, and evaluate whether or not it should be saved, but not enough time that you’re a fundamentally different person by the time you stumble back across it 30 .

In a world with expiration by default in place, what would change? On a practical level, we would get more mileage out of less computing power. We’d be going from a disposable and greedy type of usage, a hoarding behaviour, to one which would recognise that if the box is full, you need to take something out of the box, instead of building infinite extensions until there’s nothing left to build with. 31 We would have a better understanding of what informs us as people because the external framework that we rely on to assist our memory would be by nature more goopy and imperfect and rounded. We would have reintroduced a more natural entropy into a digital context, and be empowered to move on from damaging patterns of behaviour — like diving into a sprawling, decades-old message log just to prove a point or to make a pain feel fresh. 32

We’d also have a more intuitive understanding of the relationship between our actual, lived, day-to-day experience and the collected data we both choose to keep, and that which we choose to publicly present in order to represent or illustrate our whole selves. Instead of a mass, unexamined, uncurated bulk of information about us languishing on the public internet for others to take at face value, we would have small collections of trinket, tokens and souvenirs that would imply a larger story than the item itself. If everyone was in the same boat, having our stories informed by the souvenirs we choose to save (rather than letting algorithms choose for us from a sea of everything we’ve ever seen, thought, or done) would encourage us to afford that same grace to others — the grace of acknowledging that there’s more behind the public presentation of curated trinkets, and that a flat profile should never be confused for the complex, expansive, whole.