A conversation with Max Fowler

November 16, 2022.

Max Fowler is an artist and programmer working with offline-first software, mycology, and community infrastructure. They are a contributor to PeachCloud, software that makes hosting peer-to-peer software on local low-power hardware more accessible. They are also a co-founder of KiezPilz, a communal fungi cultivation group based in Berlin. They were a student at the School For Poetic Computation (SFPC) in 2016 and later an Assistant Teacher for Melanie Hoff’s Digital Love Languages at SFPC. They are one of the admins of sunbeam.city and are interested in foraging, flip-phones, rust, and HTML.

MAHM: During one of our talks during office hours for Digital Love Languages, I remember I wrote in my sketchbook, "the internet does not exist." In the first sentence from the publication of the same title, editors of e-flux journal write: "It has no shape. It has no face, just this name that describes everything and nothing at the same time." To help frame our discussion on self-hosted servers, I was wondering if you could introduce self-servers and their distinction from "the cloud."

MF: The internet is just computers communicating. So, if I have a few computers over here in communication, that's the network. And if there's another group of computers somewhere else in communication, that's also a network. The internet is just the inter-network combining of these different networks. But at the same time, in common usage, sometimes that's lost, and that decentralized aspect of its fundamental structure is replaced with this single entity. You're either connected to the internet or you're not connected to the internet.

With regard to the “cloud,” that's a deceptive word. It sounds harmless and like it's everywhere and nowhere. I appreciate that quote and people saying, "the cloud is just other people's computers" — these reminders that the cloud does ultimately take place in physical space; even if it can be perceived as this ethereal non-material thing, it actually still exists in the material world.

A self-hosted or community-hosted server is a server that you or your community are the caretaker/administrator of. This could be in “the cloud,” using a server provided by a company like DigitalOcean, where you are the digital caretaker, but the cloud provider still owns and maintains the actual hardware, or it could be on local hardware such as a computer you have physical access to, where you are both the physical and digital caretaker.

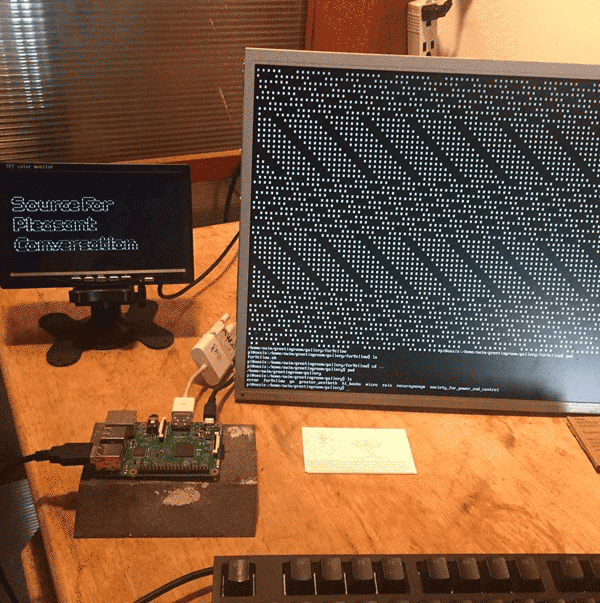

MAHM: I'm curious about your initial interest in hosting your own server. I know you've been thinking about self-hosted servers for some time now using Raspberry Pis (single-board computers). MF: Originally, I was interested in Raspberry Pis when I did a project called Oasis, which was an SSH-based textual world — Secure Shell (SSH%20and%20share%20data.)) is a way to remotely log in to a computer through the command line — where you could SSH into this Pi with other people at the same time and move around through the folders that were like rooms such as a kitchen or a living room. One part of it that I was interested in was the way a folder structure could resemble a physical space where we create physical and mental models. The other part was in the physicality of the Pi. By SSHing into this Pi, you could literally see the place where you were going. It felt like that was a kind of magic. At that point, I wasn't thinking as much about the politics of servers and physical infrastructure, but this was the first seed that computing happens in a place somewhere.

Oasis by Max Fowler, 2017 MAHM: That was at SFPC, right? I also had a similar experience when I was there.

MF: They talked about the work of Ingrid Burrington a lot at SFPC. She’s getting into similar things, too, going on infrastructure walks and bringing visibility to data centers. I appreciate Ingrid's work bringing light to the way the internet works. I've also always been interested in projects that try to build alternatives. That led to my interest in asking, “if we aren't going to have these hidden data centers, what other possibilities could there be?”

MAHM: You have a great Are.na channel called Sovereign Hardware. Was that concept something you were thinking through as you contributed to PeachCloud?

MF: Yeah. I think sovereignty is a really big topic that, like decentralization, can mean different things in different contexts, but it still really resonates with me. I can feel the difference between things that you have some autonomy over and something like using the Facebook interface. Something changes the next day, and you just accept the new conditions without anyone asking you or giving you any option to do something different.

I've been thinking of a concrete, maybe silly, example with bicycles. I've been thinking about renting a bike versus owning a bike. How with owning a bike, I feel a lot of freedom. I want to push back against the word “owning,” too. Sometimes I'm more like a steward than an owner. One definition I've heard of ownership is the right to destroy. It's not that if I own something, I can do whatever I want and not think about how it relates to things larger than myself. But it's more that there's no one micromanaging that process of stewardship. If you're renting, it's a dependence that will accumulate, and it changes your relationship with how you think about it.

MAHM: Owning a bike also comes with the act of maintenance, and this may be getting to the "right to repair." It comes with stewarding, compared to being denied to modify accordingly.

MF: This thing about repairing also has been on my mind. You mentioned previously the pedagogic aspect of people or communities running their own servers. And I also see a parallel there with bicycles that as you steward it, you learn to repair it. The fact that I can change my tires and have some basic ideas about what's happening with my bike gives me more autonomy. I could say the same thing with servers. That said, I don't think I want to be in a world where everyone is an expert server admin. There are different degrees of the relationship that are more intimate than the current form, where you don't even know that the server exists.

It's almost like when we jump to the global or national or even city level, there are different dynamics at play and different levels of trust and context. And in those places, it seems to me like more capitalist ways of relating to each other—or not the only way, but they're more relevant. But almost everyone has an experience with their friend group or their family, or some smaller space, of a non-capital-based way of relating where you just share food or give things to people, and you're not thinking about what you get back. Then there are these middle areas where we're like creating some type of new community or network where we're also able to practice sharing. MAHM: Not everyone will run their own server, as you mentioned. So how do you imagine the greater extent of these server stewardship practices and how they might exist in the future?

MF: I don't think we need to come up with solutions forever. Things can be more temporary instead of looking for the perfect mega-solution. A lot of the ethos of Silicon Valley is to come up with these mega-solutions that will be global and last for a long time. I'm looking for more contextual solutions. A project I'm excited about is Co-op Cloud, which is more aligned with the idea that not everyone's going to be their own server admin. While we were working on PeachCloud, which is more Scuttlebutt specific, some projects have emerged and grown with a similar ethos, such as Yunohost, which makes it easy for people to run their own infrastructure. Or, in the case of Co-op Cloud, for cooperatives to provide infrastructure for their community. I think this is a beautiful model because you can get this service from people you know and trust and who are part of your community. And then, through the software, they're sharing this knowledge with other groups doing the same thing, but each group is still independent. I also think about crisis, and how right now, there's this feeling of abundance of the internet and energy. It seems like a pain to self-host when you could get something premium instead. But in a crisis, and actually, even now, there are lots of people who are not served by the tools that are mainstream. I think that will only continue. I’m even questioning the word “crisis” because a crisis is what you imagine as a break from the status quo, assuming that the status quo is serving everyone.

MAHM: That makes me think of digital accessibility. I was able to talk to Redes por la Diversidad, Equidad y Sustentabilidad A.C. when in Mexico City. They work with Indigenous communities to determine the digital infrastructure that’s best for them, and it’s not always to be connected to the World Wide Web. They have the right to de-link and have their own networks and for their community to make that decision themselves. You've shared Panayotis Antoniadis's text Co-Designing Economies in Transition, specifically the chapter "The Organic Internet: Building Communications Networks from the Grassroots". I want to redirect this text back to you, where Panayotis asks: "Should big corporations like Facebook or Google be allowed to offer connectivity in exchange for more power over the Internet itself, or should connectivity be considered a ‘commons,’ provided by the people for the people?"

MF:

Have you checked out the work of Luandro? He's doing some beautiful work with community networks and Indigenous communities. There's one community he was working with where they specifically wanted to have periods where the internet was blocked. As you were saying, they didn't want to be fully linked. So he was helping them get a connection where elders in the community could set the terms of when there would be access and when there wouldn't. Some information purists would push back against that, but I think it's really beautiful. And it was funny that their wish converged with my own wishes, too. I'm grateful whenever I'm in places where there are community agreements not to have phones in certain places.MAHM: There seems to be renewed interest in people stewarding their own self-hosted servers. Is it a coincidence that it’s happening in parallel with the promises of Web3? Perhaps this ties into what people like Laurel Schwulst have described as Web0.

MF: I can say that on Scuttlebutt, the Fediverse, and Yunohost, there's some pushback against trying to use these blockchain-based solutions for everything. There are a few different angles of criticism. One of them is just asking, is there a need for a global blockchain and a singular database? Versus systems like Scuttlebutt that are decentralized in that not everyone has the exact same data in every place, and maybe that allows for more contextual internet, kind of like you were discussing. Maybe Indigenous communities have networks that are not completely the same as the other parts of the network, and also non-Indigenous people might want that as well. That does relate to building local trust because you can have more contextual areas of trust. I'm interested in blockchain things too, and I think there could be a place for these more global consensuses and shared agreements of how things work that are cryptographically verified. But I'm also interested in the non-digital. I like things that can seamlessly degrade into being non-digital. That's my biggest interest right now.

MAHM: Can you say more about "seamlessly degrading into being non-digital"?

MF: I like it if my system, or the way we work together, doesn't one hundred percent require us to use computers. I'm interested in minimal computing or even anti-computing — ways of using computers that bring us to use them less instead of more, which I would also largely put under the lens of "appropriate technology," but instead of using a blockchain for everything, just using the number of resources you need to do whatever it is you're trying to do. A friend Trav pointed me to an Ursula Le Guin quote. Have you heard this one? Trav says:

"In one of the more obscure Ursula K Le Guin, Always Coming Home, there was a passage that has always stuck with me. She's describing a hypothetical society where (to paraphrase) they had eventually come to the realization that: 'the computer, once invented, could not be un-invented.' They put most of the storage on the moon, most of the processing power in a network of satellites, and in every village, there was a hut with a dumb terminal. The vast majority of the population didn't need computer skills, only the handful of people whose lifetime tenured position was to maintain the hut and the terminal. The only 'useful' function provided by the terminal was you could tell it what you had and what you wanted, and if there were people nearby with complementary needs and wants, it would tell you which direction to walk.”

I liked this. Not that we would exactly build that. It's just a very minimal computing setup. It would give you what you need and not suck you into a spiral of using it more and more.

MAHM: I love that it's not only situated within needs — at least the way it's described here — but is also implying that it's situated in some vernacular cosmology.

MF: Can you say what you meant about cosmology?

MAHM: I’m actually taking a class right now called “Global South Cosmologies and Epistemologies” with Chakanetsa Mavhunga. “Global South” here is not South as in geography but as an experience. The class is essentially looking at local knowledge to decenter what Europe centered. This relates to what I was talking about with Redes por la Diversidad, Equidad y Sustentabilidad. They made a publication titled "¿Y si repensamos las tecnologías para la comunicación?” or "And if we rethink communication technologies?" On the cover, they draw a beautiful diagram of a network interconnected with maize. During a conversation with them, they talked about how one of the Indigenous communities understood the intranet in relation to their milpas, a multispecies and planetary model of interdependency.

Before we wrap up, I’m thinking about Zach Mandeville's essay “Sacred Servers,” where he ends the text imagining a town with many nodes or local servers — how each node has its own personality built up over generations. One is a library of downloadable software that lives next door to him, and another is a server that holds the memoir of their grandmother.

MF: I love that essay and vividly imagining what that might look like, particularly this calling in of the sacred and thinking about where you store stuff and the energy involved in that and how weird and estranging it is to put stuff in a data center, especially if you have personal or communal sacred and valuable memories and materials. A lot of this stuff about rehearsing ways of stewarding is an image that comes up for me. I would love to see community spaces, libraries, and elderly homes, somewhere where they have a server, and the people who take care of the space, taking care of the server — for it to become one of the tasks that are shared, similar to cleaning or cooking or composting the shit. That would just become a communal ritual that people learn how to do and share the knowledge and keep it alive through practicing it.